To Pulse, One Must Love: On Kim Dotty Hachmann’s Pulsar

Essay by Natasha Marzliak, Curator, Art Critic, Professor of Art History and Aesthetics, and Associate Editor of Art Style International Magazine

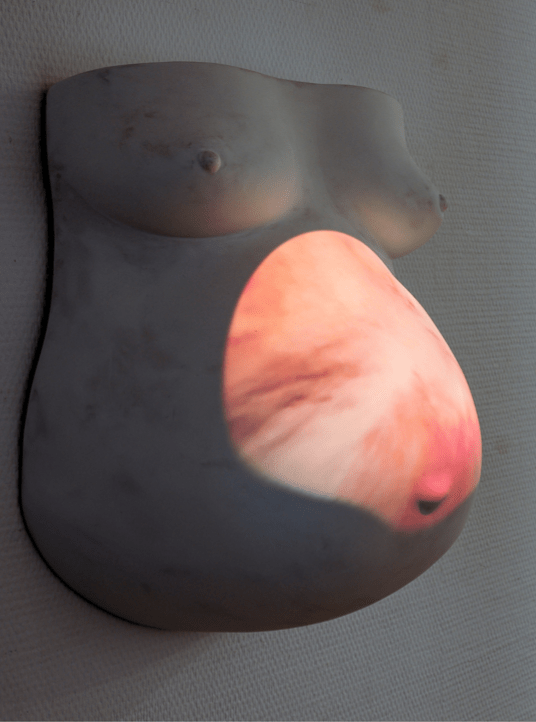

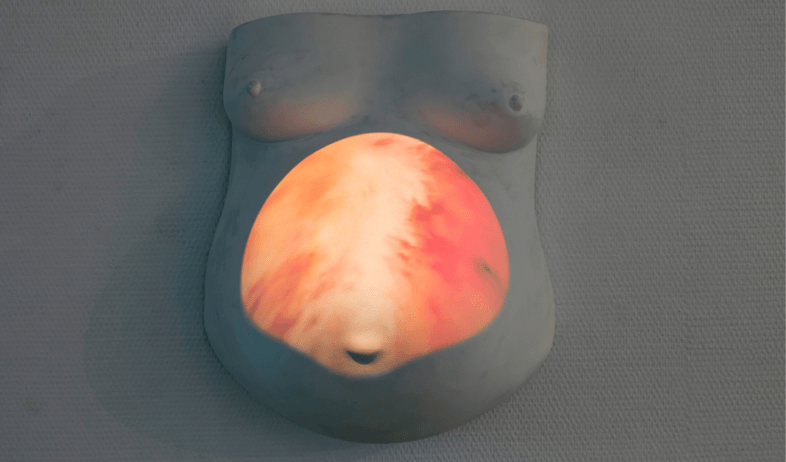

About the artwork »Pulsar« (2008–2024) by Kim Dotty Hachmann, video installation, 120 x 120 cm, white plaster cast from silicone mold, AI-generated video projection, sound; on view at Ausstellung „Aus heiterem Himmel“, November 1–23, 2025, Verein Berliner Künstler in cooperation with the A und A Kulturstiftung, part of the selection of artists nominated for the Kunstpreis für Bildende Kunst 2025.

»Pulsar« (2008–2024) by Kim Dotty Hachmann is a liminal artwork, situated in a threshold space: it invites the viewer to the impossible experience of seeing birth through the eyes of the one being born. This perceptual shift, created through the sculptural womb receiving a video projection generated by artificial intelligence, does more than represent birth; it invites the viewer to inhabit this state of coming into being in a way that is both intimate and disorienting. What is normally assumed as a self-evident beginning – the arrival into the world – is rendered strange, making the body, time, and relational conditions visible as active, contested dimensions.

The choice of the title, Pulsar, emerges naturally from this experience of threshold and passage. Coming from Latin-based languages – Portuguese and Spanish – the word carries the sense of pulsing, a rhythmic insistence that is felt physically and intuitively. Its pronunciation and cadence resonate with the ongoing, insistent force of life, preparing the viewer for the embodied experience of the installation that follows.

The white plaster womb, cast from a silicone model, functions simultaneously as membrane and surface. In this three-dimensional object, the video projection is not merely an overlay of image but a spatial inscription that transforms the volume into a body in flux, where presence, observation, and corporeality intersect. This practice, highly relevant in contemporary art, sits at the frontier of video-mapping and object-based installation: by projecting onto the womb, Hachmann creates a hybrid materiality in which digital imagery interacts with physical form, making the act of seeing inseparable from the act of being present. The body pulses alongside the viewer who experiences it in that moment, not as record or memory, but as a shared, in-the-moment event. In dialogue with the exhibition’s title, Aus heiterem Himmel, birth appears as something that comes unexpectedly – from nothing, yet also carrying the weight of a larger cosmology.

The sound layer is structuring for the work. Ancestral female chants are delivered through headphones, creating a focused listening space. This sound recalls practices that Western history medicalized, silenced, or disciplined, restoring birth to a ritual, communal, and cosmological dimension. Hachmann describes this experience as a “trance of self-empowerment,” repositioning maternity beyond idealization or stigmatization and making visible the agency of the female body. The artist’s declaration that “my female body is a gift” situates the work within a lineage of feminist practices that reclaim the maternal body from historical regimes of control and appropriation. In this sense, Hachmann’s gesture resonates with Mary Kelly’s pioneering works of the 1970s: in Anteparto (1973), Kelly transformed intimate traces of pregnancy into analytical records, and in Post-Partum Document(1973–79), she displaced the mother’s body from an object of representation to a site of enunciation, exposing how authority, authorship, and visibility are structured within patriarchal culture.

The artificial intelligence[1] does not function as a neutral technical device; it acts as a proposer of ethical and existential questions. The imagery it generates occupies an in-between space: it is neither memory, nor representation, nor pure fiction. It attempts to imagine what cannot be remembered – the intrauterine space, the act of coming into the world – and in doing so, raises questions about how technology engages with the body, life, and the limits between human and nonhuman.

The title of this essay, »It Takes Love to Be Able to Pulse«, summarizes the ethical dimension the work evokes. The pulse is not only a heartbeat, but a cosmic vibration; a condition of shared existence, dependent on care, connection, and presence. Love here is not sentimentality, but a political, relational, and cosmogonic force. It is what sustains life and the very possibility of entering the world.

»Pulsar« returns us to the moment before consciousness, before language, before the world as we see it. At its core is the understanding that birth is not simply past, but a continual condition: we are always being launched into the world, always crossing membranes, always pulsating. The work opens a space onto this impossible moment, the impossibility of now, and in doing so, allows the viewer to recognize themselves as a body that vibrates, that is traversed, that inhabits this state of coming into being. Hachmann offers this passage as a form of reunion: with beginnings, with the body, with ancestry, and with the cosmos. In the end t reminds us that the pulse of life does not exist alone. To Pulse, One Must Love.

[1] The work was first presented in Next Level Sht* (2024) at INSELGALERIE Berlin, curated by the artist and Miriam Smidt, an annual exhibition dedicated to artistic practices engaging with artificial intelligence.

INSELGALERIE Berlin

Petersburger Street. 76 A, 10249 Berlin

www.inselgalerie-berlin.de

Publishing in Art Style Magazine is free of charge for anyone. There are no article processing charges or other publication fees. Art Style Magazine is independent and supports the Open Access Movement. The editors of Art Style Magazine cannot be held responsible for errors or any consequences arising from the use of information contained in essays and articles published on the Art Style Magazine’s website and editions. Authors agree to the terms and conditions and assure that their submissions are free of third parties’ rights. The views and opinions expressed in the essays and articles are those of the author and do not reflect the views of Art Style Magazine. The authors of Art Style Magazine’s essays and articles are responsible for its content. The Art Style Magazine‘s website provides links to third-party websites. However, the magazine is not responsible for the contents of those linked sites, nor for any link contained in the linked site content of external Internet sites (see Terms & Conditions).