Next Level Sh*t: Digital Works in a (Still) Analog World, curated by Kim Kim Dotty Hachmann and Miriam Smidt, INSELGALERIE in Berlin

Exhibition: Next Level Sh*t | INSELGALERIE, Berlin | until 24 January 2026

Essay by Natasha Marzliak, Curator, Art Critic, Professor of Art History and Aesthetics, and Associate Editor of Art Style International Magazine

In Next Level Sh*t – digital works in an analog world, curated by Kim Dotty Hachmann and Miriam Smidt, INSELGALERIE in Berlin unfolds as a continuous site of tension between the physical and the virtual, the artisanal and the algorithmic, the human gesture and technological mediation. The addition of (still) to the subtitle, (a still analog world), does not belong to the exhibition’s official title, but serves, in this essay, as a critical inflection that I propose, a deliberate gesture to name a liminal moment, in which we live, a suspended, unstable temporality where the analog persists not as nostalgic residue but as an active field of contestation.

We inhabit a world increasingly saturated with synthetic images, AI-generated visualities, and regimes of hyperproduction that progressively hollow out the gaze. In this context, the question quietly underpinning the exhibition is not how to reject the digital, but how to continue producing meaning, experience, and relationality in an ever more fictive world, without losing sight of the fact that our relationships, affects, and corporealities remain profoundly “analog”. It is precisely within this interstice that the exhibition operates.

The curatorial structure resists a linear narrative of progression from analog to digital, favouring an experience composed of infiltrations, returns, echoes, and mirrorings, an expanded present in which matter and code no longer separate cleanly, and where the vision is constantly mediated by interfaces, platforms, and automated systems.

This logic manifests immediately upon entry, a print of an eye generated by artificial intelligence by Miriam Smidt greets the visitor, a static eye observing from the outset, functioning not as scenography but as a conceptual device, a non-human perception that precedes and frames the visitor’s experience. At the far right of the gallery, in the bar, a space of conviviality, distraction, and inebriation of Bacchus, the same eye returns in motion as an AI-generated video. Between print and video, between still and moving image, a silent circuit emerges that structures the entire exhibition, a continuous oscillation between presence and simulation, between what remains materially anchored and what flows, permeated by artificial intelligence.

The decision to begin the exhibition route on the right-hand side of the gallery, a deliberate choice of mine, reinforces this ambiguity. While this section hosts predominantly physical works, collages, paintings, prints, and objects, it does not constitute a sanctuary from the digital. The view has already been shaped at entry. The digital does not appear as a destination, but as a latent layer permeating the space, even where paper, paint, and matter remain tangible.

Within this liminal zone, Miriam Smidt’s works operate as a recurring conceptual axis. In Me, Myself, AI (2024), her images function as indices of subjectivity in constant modulation. Life, death, healing, and transformation do not emerge as opposites, but as transitional, fluid conditions.

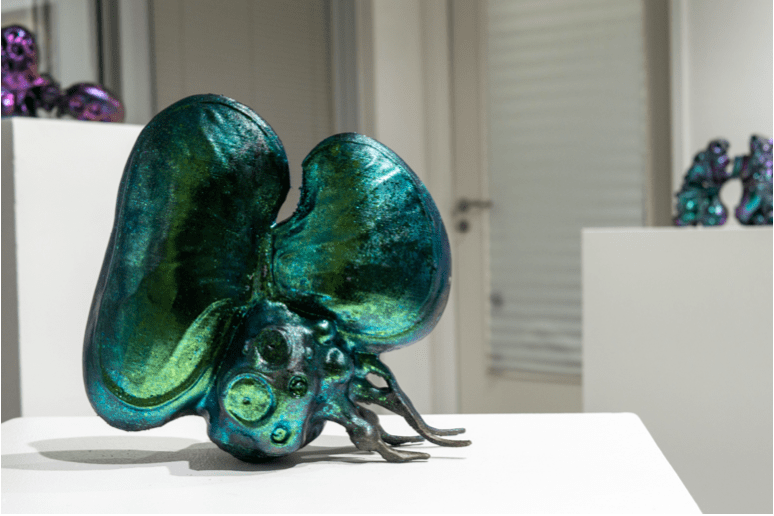

This exploration materialises three-dimensionally in the series Update Us (2025), realised in 3D printing. Glandula Empathiae, Memoria Triplex, and Glandula Dissolutrix designate fictional organs, as if the human body needed to be redesigned to survive a world saturated with informational flows. The AI eye accompanying the visitor from entry to exit functions as an amplified metaphor, an organ without a fixed body, observing, learning, and returning images.

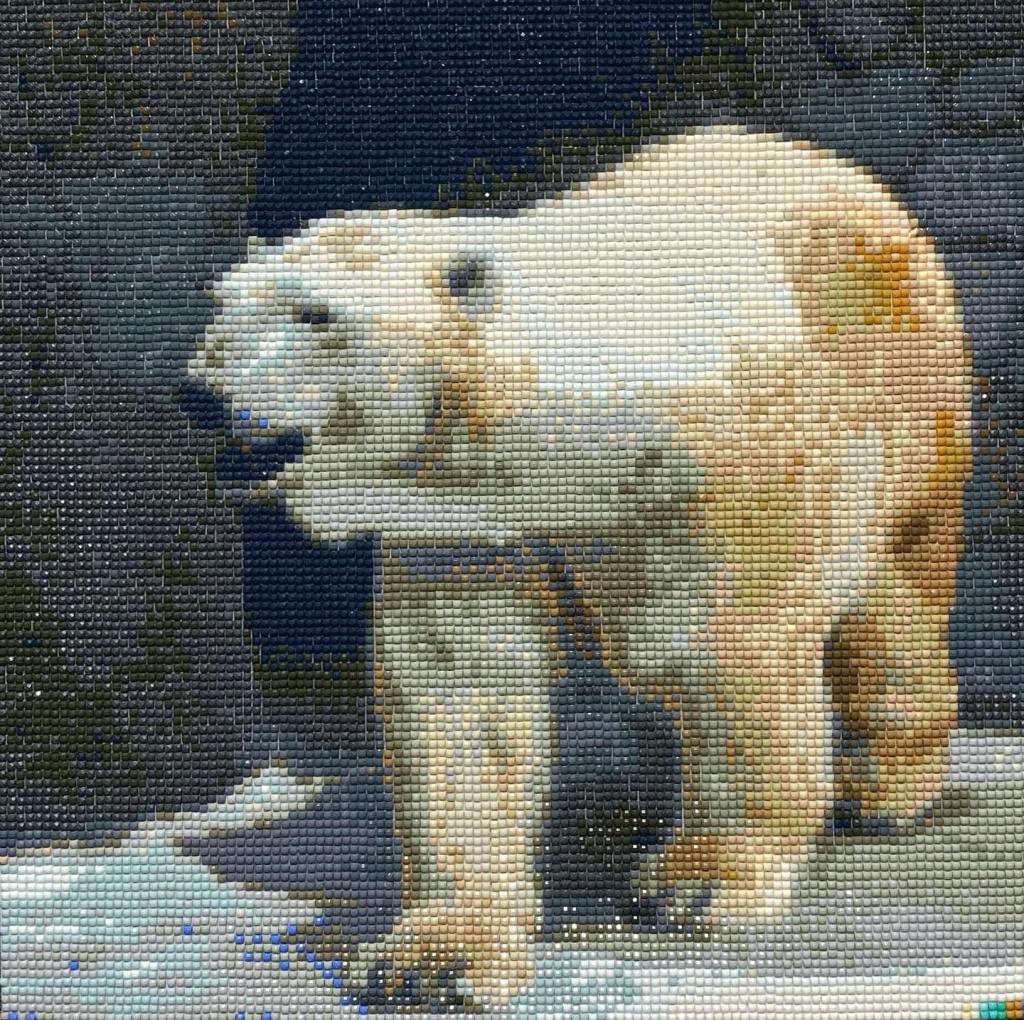

Also on the right-hand side, Swaantje Güntzel’s works offer a rigorous critique of contemporary landscape imagery. In Eisbär / Diamond Painting II and the installation Arctic Illusion (2025), popular artisanal techniques interrogate the aestheticisation of environmental catastrophe and the reproduction of stereotypical visions of the Arctic, now amplified through databases and AI-generated imagery. Dialogue with a chatbot in Arctic Illusion exposes the gulf between material urgency and discursive simulation, often more readily consumed than translated into transformative action.

Maja Rohwetter’s collages and paintings establish a poetics of fragmentation. In Paradise #1 and Paradise #2 (2024), as well as in Gemischte Gefühle #19 (2025), paradise appears as a precarious construction, composed of cut-outs, overlays, and ambiguous affective registers. The logic of collage dialogues directly with the aesthetics of digital interfaces, feeds, windows, and layers, while manual execution asserts the corporeal presence of the artist. In In the Vicinity of Life Parts (2011), painting extends beyond the canvas, entering processes of virtualisation that destabilise the analog rather than negating it, transforming the medium itself into a field of ontological inquiry.

Moving toward the left-hand side, the exhibition brings into view what until then had operated as a subterranean layer, the digital emerging as a space in its own right, experienced through the curators’ careful scrutiny. Here, NFTs from Kika Nicolela’s collection assume a central role. Navigation through this territory remains cautious, and rightly so. The infrastructures underpinning the crypto universe are neither neutral nor free from environmental, economic, or political contradictions. Yet within this context, NFTs do not present themselves as redemptive nor as absolute villains. They emerge as symptoms of our times, spectral spaces in which images, affects, and experiences exist without stable physical anchoring.

In A Working Day (2025), Estelle Flores offers a quiet observation of labour time within the digital economy. An ordinary day is transformed into an aesthetic unit, a datum, a record. The work neither accuses nor celebrates, but observes. As an NFT, the piece amplifies this ambiguity: lived time is captured, edited, and circulated. What precisely is being archived here, a day of work, or the experience of existing under continuous regimes of productivity?

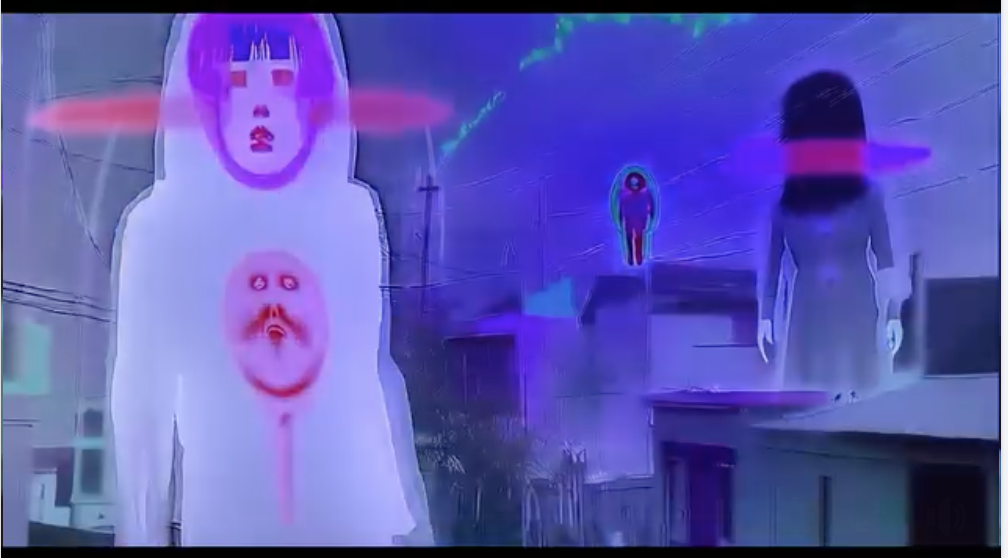

In the feels – seventeen aka. stepping through the warp that I can only see (2025), the artist littlecakes constructs a brief yet intensely sensory video. The work operates as a fragmented affective experience, marked by unstable rhythms and discontinuous perceptions. The “warp” of the title is not merely visual or temporal, but psychic, an internal displacement, difficult to articulate, referring to emotional states mediated through the digital. The piece inhabits a space between presence and disappearance, like a ghost that manifests only as flow.

At the conceptual core of the exhibition, Ann Schomburg makes explicit what quietly permeates the entire path, infrastructures of intimacy. In CATThexis (2025), a complex and striking installation, visitors encounter a series of hybrid devices, physical works, a telephone through which they can “speak” to a cat, mirrors, digital interfaces, and a website narrating a futuristic story about human-animal relations. The narrative recalls elements from the film Minority Report (2002), in which technology monitors every gesture and glance. Visitors care for the animal, yet by failing to follow certain rules or protocols imposed by the digital control structure, they lose it. This tension between care, responsibility, and technological surveillance generates an immersive experience blending affection, frustration, and surprise, revealing how algorithms, digital systems, and attention economies shape relationships, desires, and visibility. Life, performance, and social practice intertwine, highlighting the active role of the visitor within the sensitive ecosystem the work constructs.

It is within this entanglement of works, languages, and media that (still), as a critical gesture, manifests its force. It does not signal nostalgia nor a refusal of the digital. It designates a heterogeneous transitional state. We are increasingly immersed in synthetic images and systems shaping perception, memory, and desire, while simultaneously relying on bodies, materials, and physical relations. The (still) marks this unstable interval, a time in which passage remains incomplete, with consequences still unresolved.

The question underpinning Level Sh*t is not new. It has arisen with the advent of photography, cinema, and video, and resurfaces now with symbolic artificial intelligence, NFTs, and digital environments: where is art headed? Perhaps the answer lies precisely in its capacity to endure. Art does not die. It appropriates, displaces, distorts, and reconfigures available media to render visible that which remains as yet unnamed.

The AI eye greeting visitors at the entrance, returning in motion at the end of the route, offers no answers. It returns the question to the visitor. Perhaps the exhibition’s subtitle, digital works in an analog world, speaks precisely to this, not a delay but a critical interval, a time necessary to think, feel, and conceptualise the observing before the analog becomes mere archive or fetish. This will not occur, as everything intertwines in the loose threads of contemporary art. Level Sh*t reminds us that we are midway along the path, and in the meantime, the responsibility to look and to think the gaze persists. It is incumbent upon us, artists, curators, critics, and audiences, to sustain this reflection.

INSELGALERIE Berlin

Petersburger Street. 76 A, 10249 Berlin

www.inselgalerie-berlin.de

Opening hours: Tue–Fri 2-7pm, Sat 1-5pm

Finissage of the show with artist talk: Sat 24th January 2-4pm

Publishing in Art Style Magazine is free of charge for anyone. There are no article processing charges or other publication fees. Art Style Magazine is independent and supports the Open Access Movement. The editors of Art Style Magazine cannot be held responsible for errors or any consequences arising from the use of information contained in essays and articles published on the Art Style Magazine’s website and editions. Authors agree to the terms and conditions and assure that their submissions are free of third parties’ rights. The views and opinions expressed in the essays and articles are those of the author and do not reflect the views of Art Style Magazine. The authors of Art Style Magazine’s essays and articles are responsible for its content. The Art Style Magazine‘s website provides links to third-party websites. However, the magazine is not responsible for the contents of those linked sites, nor for any link contained in the linked site content of external Internet sites (see Terms & Conditions).