The Boys Are Alright: Feminist Interventions in Domestic and Public Space

Review of The Boys Are Alright – Solo Exhibition by Kim Dotty Hachmann

Curated and written by Natasha Marzliak

Motherhood and art share an intimate, often invisible dialogue: both demand presence, attention, and care, and both shape worlds. Yet a mother who is also an artist must navigate impossible demands, constantly pulled in multiple directions. In Kim Dotty Hachmann’s work, this tension becomes visible, showing how creativity and caregiving intertwine, collide, and produce unexpected forms of expression. Her practice navigates the delicate interplay between intimacy and public display, domesticity and artistic gesture. In her solo exhibition The Boys Are Alright, presented at Michaela Helfrich Gallery in Charlottenburg, Berlin (August 1–12, 2025), Hachmann presented over a decade of work at the intersection of art and motherhood — a space rich with ontological, ethical, and political inquiry. Her video and photographic series transcend mere depiction, positioning her children as active collaborators who shape rhythms, activate environments, and imbue the everyday with performative intensity. In Hachmann’s lens, the domestic sphere, the urban landscape of Berlin, and the quotidian are transformed into charged spaces where distinctions between maternal and political corporeality subtly dissolve, rendering the familiar simultaneously intimate, strange, and tinged with humor.

The family dynamic is brazenly foregrounded. Rather than sanitizing domestic scenes, Hachmann elevates the spontaneous and the unvarnished: the inherent disorder, the rhythms of daily life, the emotional complexities, and the delicate structures of care. Motherhood is not portrayed as a limitation but rather as a potent catalyst for creative endeavor. Furthermore, the work extends beyond a simple representation of parenthood or childhood, engaging with layered historical, social, and systemic concerns. Top Terrorist (2010) employs toy guns to deconstruct the ways in which violence and gender roles are subtly rehearsed in childhood play. The piece echoes Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery (USA, 1903), particularly its iconic final scene where a bandit confronts the viewer. Unlike the early Western, which established a genre of cinematic masculinity, Hachmann recontextualizes children’s play as a stage where the boundaries between menace and innocence become fluid.

Concrete Speed (2011) juxtaposes a child’s body with the rigid forms of modernist architecture, highlighting the inherent tension between structured environments and the unpredictable spontaneity of youth. Resonating with this exploration, Rise & Fall (2011) depicts two nude children engaged in play on a bunk bed, yet strikingly adorned with oxygen masks. This visual paradox speaks to themes of vulnerability, control, and the pervasive influence of unseen forces. The scene, far from being tragic, possesses an uncanny playfulness: a scenario that feels both ordinary and subtly dystopian, humorous yet disquieting. This exemplifies Hachmann’s distinctive approach—the subtle estrangement of the commonplace, rendered with a precise, understated irony.

Hachmann’s later works further develop this logic of estrangement. Box (2012) illustrates children transforming confined spaces, specifically dog kennels, into arenas of movement and imaginative invention, thereby questioning the demarcation between restriction and freedom. This work, filmed outside a storefront, captures children repurposing cages into dynamic zones—climbing, entering, and transgressing perceived boundaries. It thoughtfully probes issues of parental oversight and the inherent, often untamed, vitality of children.

Beneath the surface of this nuanced engagement lies a trenchant critique. Burnout (2012) reframes maternal exhaustion not as a romanticized sacrifice but as a direct consequence of systemic overload. In a poignant counterpoint, Trashy Islands (2012) encapsulates fragments of cellphone footage within a miniature jewelry box—intimate moments of children rolling in sand, blowing bubbles, or gazing at a church ceiling. These fleeting, ephemeral gestures form a private reliquary of joy, offering a tender antidote to the theme of exhaustion.

Familienbande – Portrait Neo, Portrait Vito (2017) redefines traditional family portraiture by synthesizing European aristocratic iconography with tribal motifs, proposing a hybrid lineage that transcends biological ties or institutional definitions. The work stages kinship not as inheritance but as invention: a performative act that unsettles the authority of genealogy and the visual codes through which power, bloodlines, and legitimacy have historically been represented. By fusing the rhetoric of European sovereignty with visual vocabularies marked as “other,” Hachmann questions the hierarchies embedded in portraiture itself — a genre long tied to the consolidation of identity, property, and patriarchal continuity. In her images, family becomes less a matter of origin than of affective codes, improvised rituals, and shared fictions — a fragile but generative space where belonging is always in motion.

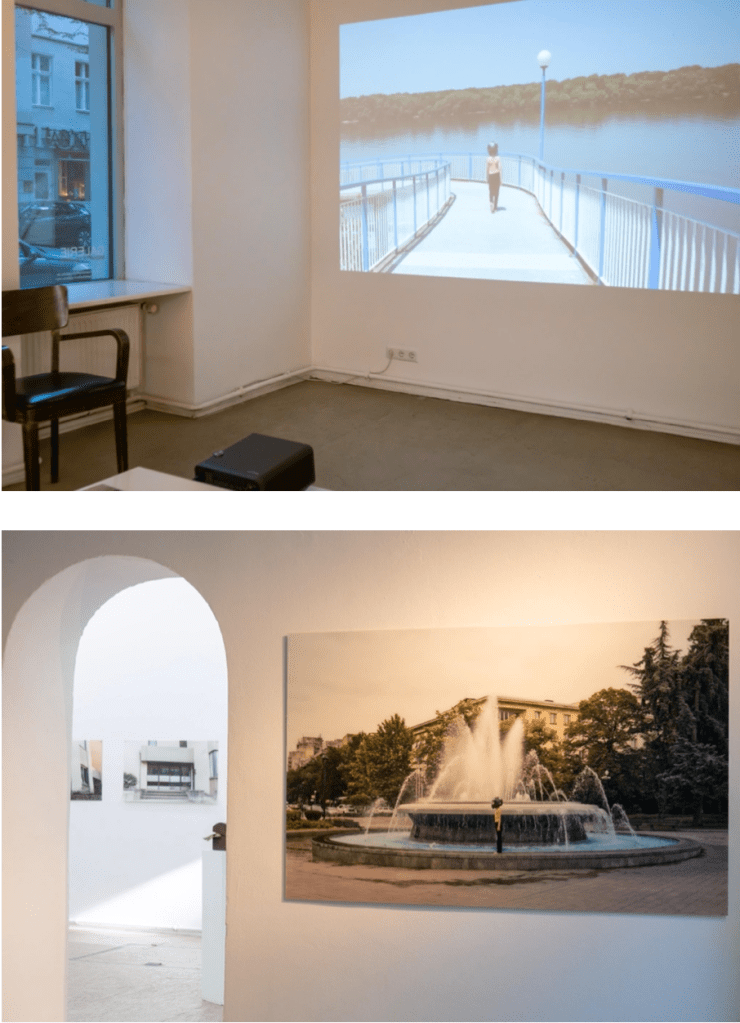

Walk Around (video, 2021) and Loading (photograph, 2022), presented as a unified installation and developed in Europe’s peripheral regions, position the child’s body as a conduit for imagination, navigating terrains situated between architectural constructs and organic landscapes. This pairing creates a visual play: in the video, water remains still, while in the photograph, the child’s body stands before a fountain where the water seems to erupt in an expression of freedom, highlighting a visual paradox.

Hachmann also engages with emerging technologies, pushing the boundaries of perception and temporality. lil bro (2024), an augmented photo-video installation featuring her youngest son exercising on a metal bar, integrates classical portraiture and chronophotography with augmented reality, creating a complex layering of moments, gestures, and rhythms. Time becomes malleable, folding past, present, and projected movement into a single experiential field, while the body registers perpetual negotiation — of gravity, space, and suspended duration. By merging analog and digital processes, Hachmann challenges the conventions of portraiture, foregrounding the flux of identity and embodiment, and exploring how emerging technologies can expand the vocabulary of the intimate, the performative, and the familial.

Hachmann wields humor as a critical instrument, fracturing mythologies of white motherhood and exposing the subtle choreography of normative gender expectations. In Me, My Boys and I (2025), she reinterprets her earlier piece Me, My Family and I (2006), casting herself as a contemporary Madonna—a domestic sovereign with vibrant pink hair, draped in a mantle evocative of Renaissance iconography. The subtle irony of this gesture subverts sacred archetypes of femininity and domestic virtue.

This exhibition marked a rite of passage. As her children — once inseparable from the fabric of her practice — begin to assert their own independence, Hachmann stepped across a threshold into a different artistic tempo. The crucible of early caregiving, with its relentless demands and accidental inspirations, gave way to another register: one less defined by immediacy. The Boys Are Alright was not an exhibition of closure, nor of simple recognition, but a provocation — a space where what lingers unsettles as much as it fascinates, where the everyday resists neat resolution, and where intimacy and strangeness coexist in uneasy, compelling proximity.

______

Natasha Marzliak, Brazilian art critic, curator, and independent researcher based in Berlin, is Associate Editor of Art Style – Art & Culture International Magazine and a freelance professional specializing in contemporary art operations, digital art/NFT, video, and photography. With a PhD in Arts from UNICAMP and a doctoral residency at Université Panthéon-Sorbonne Paris 1, her academic trajectory includes a postdoctoral position at Freie Universität Berlin, tenure as Tenure-track Professor at UFAM, and Adjunct Professorship at PUC-Campinas. Her work explores aesthetics, art history, and visual culture, with emphasis on postcolonial and decolonial studies, intersectional theory, and feminist and queer politics. Portfolio: https://natasha-marzliak.my.canva.site/

______

Publishing in Art Style Magazine is free of charge for anyone. There are no article processing charges or other publication fees. Art Style Magazine is independent and supports the Open Access Movement. The editors of Art Style Magazine cannot be held responsible for errors or any consequences arising from the use of information contained in essays and articles published on the Art Style Magazine’s website and editions. Authors agree to the terms and conditions and assure that their submissions are free of third parties’ rights. The views and opinions expressed in the essays and articles are those of the author and do not reflect the views of Art Style Magazine. The authors of Art Style Magazine’s essays and articles are responsible for its content. The Art Style Magazine‘s website provides links to third-party websites. However, the magazine is not responsible for the contents of those linked sites, nor for any link contained in the linked site content of external Internet sites (see Terms & Conditions).