Dancing in the Collapse of Constellations: Shiri Mordechay’s Unspoiled Nature

By Natasha Marzliak

Writing this essay cost me my sobriety. And perhaps that was the inevitable price — or the necessary ritual — to enter the universe Shiri Mordechay reveals. She excavates worlds, digging deep through the grotesque and the hallucinatory. The exhibition My Unspoiled Nature, which was on view at Serious Topics gallery (Los Angeles, CA) between May and June 2025, is a dive into the textures of sensation, the instability of form, and the haunted politics of visuality.

In moving from paper and watercolor to canvas, acrylic, and oil, Shiri shifts from a fluid and intuitive gesture to a more visceral terrain, where painting becomes a site of struggle — between body and surface, between visibility and disappearance, between the fleeting and the condensed time of paint. But this is not a matter of dualities; what she brings forth resists taming at every turn. Something in the baroque insistence of her interwoven bodies — in the viscosity and gravitational pull of the paint — calls for the abandonment of any formalized or sanitized vocabulary. The thick matter of painting does not merely cover the canvas — it embodies struggle: I hit the painting, and it hits me back, in the artist’s words. It’s a fight. A demand for fierce physicality. That’s why I write between sips of a red wine called Zeus, like someone who drinks and sees in those image-compositions a storm, a collapse of consciousness, and — why not say it — a sublime? It is not a method for reading images. It is possession.

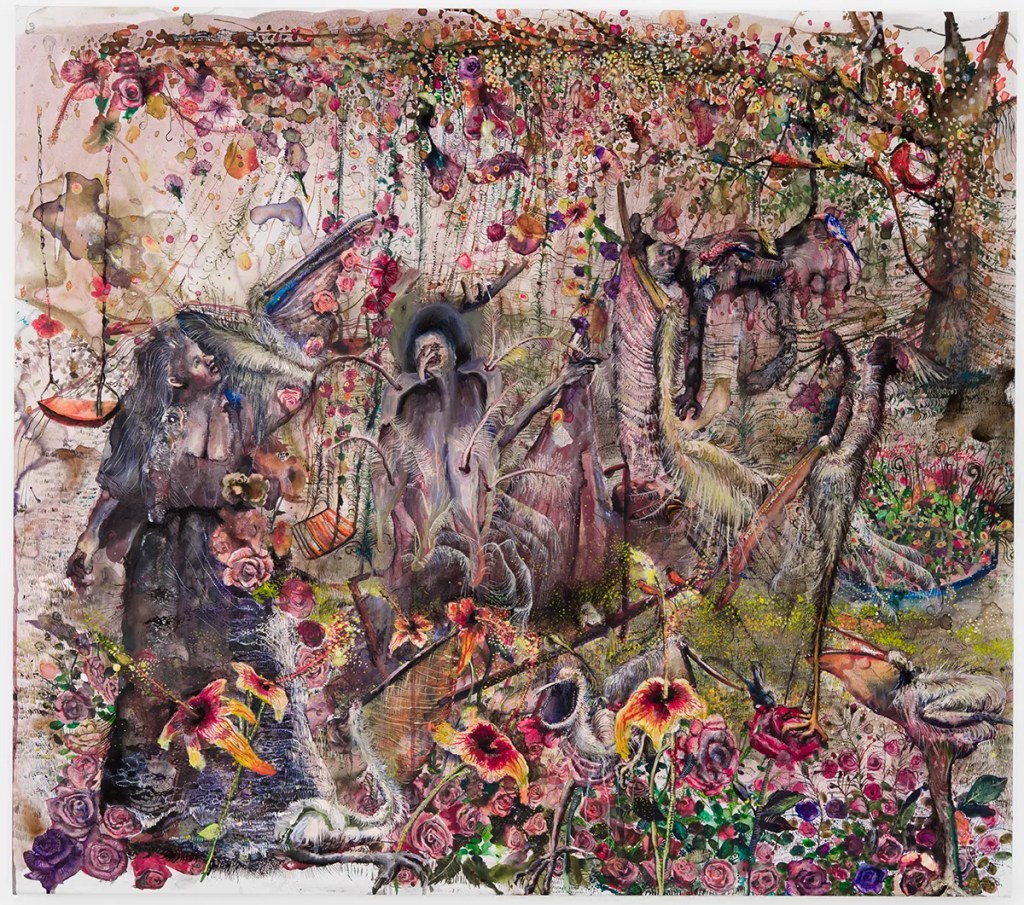

The paintings — for example, The Garden I Keep, Behind the Sun, I Can Fly in the Dark, Masked with Hunger, and Sunday Sisters, all from 2025 — impose themselves like open wounds in the field of representation, carnival apparitions that disrupt the illusion of stability we so desperately cling to. In them, the body is always more than human — it is beast, trauma, secretion, ancestry. Instead of clarity, there is fraying. Instead of purity, a crossroads. An affectionate carnage in a monstrous feast. The bodies painted by Shiri are not subjects but zones of passage, fields of friction between desire and violence, between spirituality and flesh. The “figures” appear as aberrant, hybrid multiplicities, vibrating between form and formlessness, as becomings that never settle. There are no identities here — only intensities.

A work that resonates deeply with this universe is The Garden of Earthly Delights, the baroque and apocalyptic triptych by Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1500–1510). Like Shiri, Bosch creates a cosmos where the body dissolves into a multiplicity of forms: humans merge with animals, monsters lurk among giant fruits, and nature becomes a living, threatening organism. It is a visual place where pleasure and dread coexist in unstable balance, where temptation turns into torture, and where the gaze gets lost amid details that never settle into a single narrative. The similarity lies in the ruin of forms, in the transgression of natural order, in a materiality that refuses to bend to modern rationality. Bosch, with his hybrid and deformed bodies, anticipates what Shiri updates and radicalizes: a painting of chaos. Both insist on disrupting the clear line of time, space, and identity, proposing affective constellations where past, present, and future overlap, and where bodies become a battlefield of forces in conflict.

The Garden of Earthly Delights and the My Unspoiled Nature series build a topology of excess: a pictorial field saturated with symbols and allusions where the human is reduced to flow — sexual, bestial, spiritual. Flesh is celebrated as a path of transcendence and fall. Flesh pulses beyond morality, in its potency of abyss and reinvention. The connection between Shiri and Bosch goes beyond the formal aspect of their murky, proliferating compositions. What also unites them is a disobedience to the architectures of order, replaced by a pictorial space where the image becomes a psychic, hallucinatory, almost oracular force. In My Unspoiled Nature, as in Bosch, there is no rest: each painting is a threshold, a passage between the erotic and the grotesque, the sublime and the amorphous. Their bodies are neither stable nor idealized — they are mutations, states of overflow.

Shiri and Bosch work with the idea of collapse as method: the collapse of form, linear narrative, and moralizing representation. While Bosch painted in an Europe marked by fear and religious control, Shiri does so in a hyper-exposed era where even the gaze has been captured by regimes of desire that shape subjectivity under neoliberal logic. Both offer a cosmology without a fixed center, where the human is just one of the forces inhabiting the scene. The grotesque here is not gratuitous excess but a politics of the flesh — a way to disrupt hierarchies of figures and meanings. In both, exuberance is also despair. The Garden of Earthly Delights, in its rapture, is the spectral ancestor of the contemporary ecstasy of My Unspoiled Nature.

Therefore, the intensity of Shiri’s images is not blind delirium. The paintings obscure and confuse — not as empty opacity, but as insurgent strategies against the instrumental rationalization of experience. It is not about representing a virgin or pure nature, but about straining the limits of the visible so that other natures (inner, spiritual, dissident) can emerge. What is at stake is not the theme of nature, but its radical indiscipline. The “unspoiled” in the exhibition’s title is ironic — referring to a nature that has not been softened to fit normative discourses. The artist resists allegorical clarity and claims the right to enigma. Thus, “unspoiled” refers to a space where the gesture can still remain untamed. It is in this interval — between the unconscious and the body, between daydream and the physical confrontation with paint — that the artist builds her ethics of the image.

Figures appear and disappear in a practice of ambiguity, of incompletion. Each canvas is a space of multiplicity and becomings — becoming-woman, becoming-landscape, becoming-spirit. These becomings are rooted in the experience of the body. The artist’s body, in contact with the material, is where the real collides with the sensible. She herself states: “oil forces me to be present, to be physical.” The gesture is political because it reaffirms the body as a field of presence, listening, and creation. Shiri — woman, Jewish, immigrant artist — operates at the heart of the North American art system with a language of her own, almost secret, that escapes hegemonic regimes of visibility. Her painting is a “line of flight,” full of strategies of survival and reconfiguration. In this light, the exhibition My Unspoiled Nature can be understood as a countercurrent to the performative cynicism of the institutional art circuit — especially in contexts like Los Angeles, where art often turns into spectacle or commodity.

Shiri subverts the speed of visual consumption. Instead, she offers images that demand time, revealing themselves gradually, like traces or apparitions. The act of painting then becomes a way to insist on another temporality — a counter-time to contemporary acceleration. The eruption of the pictorial unconscious — between strokes, remnants, and interruptions — is a refusal of reason as totality. Shiri does not paint schemas; she engages with affective, symbolic, and bodily constellations, where experience is closer to dreaming than waking. The resulting pictorial field contains lapses of the unconscious, moments of rupture against the pressure for clarity, transparency, and efficiency.

In a landscape saturated by overstimulating visualities, this exhibition offers not a contemplative pause, but a deliberate loss of consciousness — like one dancing at the edge of language, challenging the viewer to relinquish quick reading, immediate meaning. One can then inhabit these pictorial events in all their vibrant potency. The violent corporeality of the canvases — where viscous accumulations impose themselves over aqueous transparencies — demands a temporality of delayed apprehension. The images propel us toward a layered reading, without narrative stability. There is no key to interpretation, only an invitation to traverse the visual as a vital act. Like dancing with the unspeakable. Like a way of saying: here I am — between chaos and gesture — and there is beauty, even (or especially) when it refuses to be captured. They are phantasmagorias whispering behind the veil, blurring the gaze with a mist of unspoken meanings.

As Didi-Huberman said, the gaze that wishes to see must accept getting lost. The viewer is summoned to live within these images. In the face of ruin — of forms, times, subjects, certainties — all that remains is to dance. Dance with the garden. Dance with disorder. Dance with visceral constellations. And embody the unconscious. Surrender to these storm-images. To write this text, I had to silence the part of myself that still wanted to explain, to allow language to be contaminated by the images, to let analysis slide along with their reverie, recognizing madness as a method of thought. I am grateful for the vertigo delirium and inebriation Shiri serves so freely — a sensory banquet.

Reference

Didi-Huberman, Georges. 2005. Confronting Images: Questioning the Ends of a Certain History of Art. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Exhibition review

My Unspoiled Nature, which was on view at Serious Topics gallery (Los Angeles, CA) between May and June 2025.

______

Natasha Marzliak, Brazilian art critic, curator, and independent researcher based in Berlin, is Associate Editor of Art Style – Art & Culture International Magazine and a freelance professional specializing in contemporary art operations, digital art/NFT, video, and photography. With a PhD in Arts from UNICAMP and a doctoral residency at Université Panthéon-Sorbonne Paris 1, her academic trajectory includes a postdoctoral position at Freie Universität Berlin, tenure as Tenure-track Professor at UFAM, and Adjunct Professorship at PUC-Campinas. Her work explores aesthetics, art history, and visual culture, with emphasis on postcolonial and decolonial studies, intersectional theory, and feminist and queer politics. Portfolio: https://natasha-marzliak.my.canva.site/

______

Publishing in Art Style Magazine is free of charge for anyone. There are no article processing charges or other publication fees. Art Style Magazine is independent and supports the Open Access Movement. The editors of Art Style Magazine cannot be held responsible for errors or any consequences arising from the use of information contained in essays and articles published on the Art Style Magazine’s website and editions. Authors agree to the terms and conditions and assure that their submissions are free of third parties’ rights. The views and opinions expressed in the essays and articles are those of the author and do not reflect the views of Art Style Magazine. The authors of Art Style Magazine’s essays and articles are responsible for its content. The Art Style Magazine‘s website provides links to third-party websites. However, the magazine is not responsible for the contents of those linked sites, nor for any link contained in the linked site content of external Internet sites (see Terms & Conditions).