Claudio Tozzi: Capital Must Not Exceed Poetry

marcelo guarnieri gallery | são paulo

Opening: March 29, 2025, from 11 am to 5 pm

Visitation: March 29 to April 30, 2025

Between March 29 and April 30, 2025, Galeria Marcelo Guarnieri presents “É necessário que o capital não exceda a poesia” (Capital must not exceed poetry), the first exhibition by artist Claudio Tozzi (São Paulo, 1944) at São Paulo location. The exhibition brings together works made by the artist between 1968 and 2024, covering more than fifty years of intense production, during which he reflected on the power of the constructed image in a visual transit between public and private space. The exhibition includes a critical text signed by curator Diego Matos.

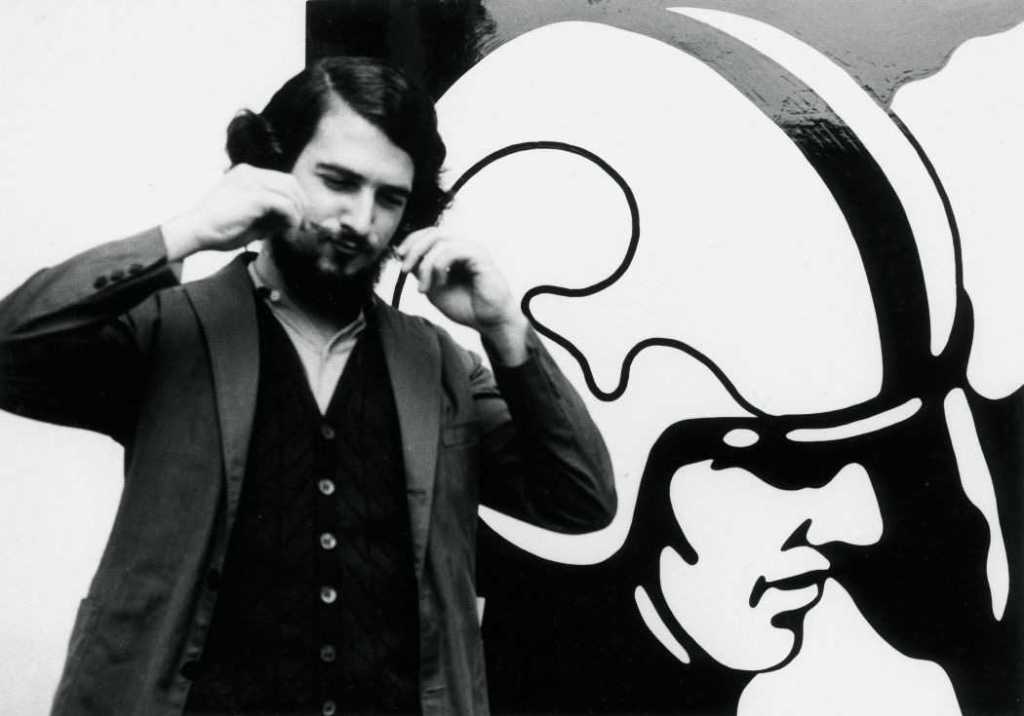

Claudio Tozzi began his artistic production in Brazil in the 1960s, approaching the language of Pop Art and the Brazilian “New Figuration” program with a critical reading of the emerging mass consumer culture that was part of a newly installed military dictatorship. In those early years, he paid special attention to symbols linked to popular militancy, such as images of protesting crowds or the face of Che Guevara, for example. The screw, a trivial object with a strong political charge when associated with the working class, runs through several decades of his production, becoming a symbol in itself within his poetics. Tozzi explores its geometry, sculptural qualities, structural function, and ability as a piercing object to articulate space-in and space-out.

His interest in the technical and visual possibilities of the reticule, initially explored through serigraphy, was reconfigured through dotted paintings or works such as “Polution” (1973), in which he explored the dot as a particle in the physical composition of the atmosphere. Still in the 1970s, as part of his investigations into compositional structures and the formation of the image in processes of integration and disintegration, he dedicated himself to the relationship between light, color, and pigment. In more recent productions, between 2022 and 2024, he explored the reticular nature of the grid format through serialized geometric compositions using materials as diverse as rubber and nylon.

Diego Mattos observes in the exhibition’s critical text: “Tozzi has never lost sight of a future perspective in which he resiliently maintains the idea: Capital must not exceed poetry. This is perhaps a reflection that functions as the conceptual anchor of his production and has been appropriated in the most recent work selected for the exhibition. […] In this way, at a time of great sensitivity to the unresolved impasses of the past, such as the discussion of the amnesty law and the struggle for memory, truth, and justice, the artist’s works gain a new injection of historical pertinence and help us to think about the real emergencies of now. Just look, for example, at the profusion of images of astronauts represented in the most varied ways in his works: a heroic figure from the times of the Cold War who continues to be an ideology in the space race and the dispute over symbolic power.

Claudio Tozzi: Capital Must Not Exceed Poetry

by Diego Matos, March 2025

A necessary preamble

To present the vast artistic output of Claudio Tozzi (São Paulo, 1944) is to take a wide-ranging flight over more than six decades of contemporary Brazilian art. In this way, the exhibition produced and organized for the context of Galeria Marcelo Guarnieri, in São Paulo, sheds light on aspects of the artist’s poetics and practice that go far beyond his works linked to the new Brazilian figuration, sometimes treated as a manifestation of national pop art.

In the exhibition, it is possible to glimpse various paths of his experimentation that reverberate to this day, linking him unquestionably to the radicalism of Brazilian art in the 1960s and 1970s. However, Tozzi has never lost sight of a future perspective, in which he resiliently maintains the idea that “capital must not exceed poetry.” This is perhaps a reflection that functions broadly as the conceptual anchor of his production and which has been appropriated in one of his most recent works, a piece that is also present in this exhibition.

From the idea of his art as a subjective reportage in the 1960s, formulated graphically, to the interferences and shuffling of object and graphic signs of the landscape under construction in the 1970s and 1980s, Tozzi’s repertoire provides us with an abundant apparatus for understanding the relations of capital and power that sustain our political-urban condition. The beginning of his artistic journey coincides with his first years as a student at the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of São Paulo (FAU-USP), and the consolidation of his first studio in partnership with his generational peers, a time of great political unrest in the early years and, soon afterward, of intense repression, censorship and terrorism with the arrival of the Brazilian civil-military dictatorship in 1964. As such, there was no way contemporary expression could pass unscathed by the facts of the country’s reality. If we revisit some themes from our recent history today, let’s also do so by looking at Brazilian artistic production.

In fact, there is a real class consciousness and a genuine interest in thinking about Brazil in all its magnitude, paving the way for modern foundations and with a clear interest in socio-cultural transformations among all its peers, not just those who orbited the FAU-USP context or even in the São Paulo art circuit. Part of this artistic class was allied to student militancy and other social movements. Moreover, even though there was a clear separation between daily activities, real contamination between merits could occur.

It was almost inevitable, at times, that an ethical and social stance would require a position that was as political as it was aesthetic. This was what Hélio Oiticica discussed in his seminal text, Brasil Diarreia (1970), in which he assessed the state of the arts in the country. At the end of the text, he wrote: “There is no such thing as ‘experimental art,’ but the experimental, which assumes not only the idea of modernity and the avant-garde but also the radical transformation in the field of prevailing concepts-values: it is something that proposes transformations in behavior-context, that swallows and dissolves coexistence.” For this reason, a considerable part of Tozzi’s production, which radicalized language, is based on Oiticica’s far-sighted approach. In the exhibition, it is possible to recognize and understand his approach being put into practice at the end of the 1960s through the photographic and historical record of the Guevara flag (1968) produced by the artist.

Its public display occurred at a happening conceived and promoted by Hélio Oiticica himself in Praça General Osório, south of Rio de Janeiro, in February 1968. Both his banner and those of his peers – Nelson Leirner, Flávio Motta, Carlos Scliar, Marcello Nitsche, Carlos Vergara, Rubens Gerchman, Glauco Rodrigues, Anna Maria Maiolino, Pietrina Checcacci, among others – were arranged on clotheslines and trees, in an organic and ephemeral action, which included performance situations and activation of these devices. It was a clear move away from institutional spaces and a collective embrace of freedom in life, between celebration and demonstration. Months later, the siege would be closed with the arrival of the most violent and limiting institutional act, AI-5. Curiously, this political condition, with its strong castrating and anti-civilization content, contributed to an even more radical handling of our contemporary art, with the most diverse fissures in the language and circuit of art itself.

A historical perspective

Far beyond the world of art, there is no way to dissociate the current debate from our cultural wealth in times of new historical reparations. In general, plastic production has walked and is walking, pari passu, with our continuous historical process and its socio-economic and cultural reverberations. Claudio Tozzi is also part of this process. His work, while exploring the intricacies of language, is also a historical document of a passage of time, even causing critics in the past to define it with a reportage value. We’ve talked about this before.

Like many of his peers, the artist was a direct victim of the structure of the state of exception. His work was destroyed and seized, and he was persecuted, interrogated, and imprisoned. One way or another, in his professional activity, Tozzi never made concessions, whether in his decades-long teaching at FAU-USP or in the coherence, ethical, and ideological rigor of his production. As a student of professor and artist Sérgio Ferro – now one of his great friends – he learned the indelible mark of the political struggle that also took place in the aesthetic field. From an intellectual tradition based on historical materialism and the radicalism of the modern ideology in the Brazilian context, he built a production with a strong spatial concern (the space of life and experience), in which he always combined graphic and formal expression with the country’s cultural reality.

Today, at a time of great sensitivity to the unresolved impasses of the past, such as the discussion of the amnesty law and the struggle for memory and truth, reparation and justice, the artist’s works gain a new injection of historical relevance and help us to think about the real emergencies of now. Between the title (text) and the work (image and material), we can see the precise choice of signs that tell us a little about the human adventure contaminated by everyday life and citizenship. In this respect, the 1971 work O retrato (The Portrait) provides an interesting reading of the meaning of “looking,” a cognitive function built far beyond the physicality of the five human senses.

It’s also enough to notice, for example, the profusion of images of astronauts represented in the most varied ways in his works: a heroic figure from Cold War times, who continues to be a human ideology in the space race and the dispute for material and immaterial power. In fact, in recent times, when we see the traumatic return of astronauts trapped in a space station for several months, the doubling of the stakes in the space race in the face of the imminent climate catastrophe, and the new romanticization of the idea of exponential and infinite growth and expansion, as well as the frightening rearmament around the world, works with clear symbolic and semiotic value like the artist’s works gain a kind of new relevance in the historical present.

Another important issue is understanding that his conceptual and practical initiatives have spanned six decades of our history, making it possible always to be sensitive to social and behavioral transformations. Beyond a poetic perception, there is always a purpose to which the drawing or project seeks to respond. I’m not talking about the utilitarian aspect of design but an intention that goes beyond the formal condition of the work. In many of these works, there is a concern to understand and problematize the very nature of the space established by architecture and urbanism, as well as its unfolding in the conditions and characteristics of the city, art’s contact with notions of territoriality, etc. All of this, however, is under the umbrella of an irreducible understanding of relief such as that given by the show’s title.

Some plastic-poetic contributions

Claudio Tozzi is responsible for a poetics of iconography, all rooted in his time. To this end, one of his longest-lasting initiatives is the canvases he produced with a keen command of reproducibility techniques, in which he examined (and continues to examine) the idea of the crowd and the power of collectivity as representation, more often than not, after photographing many of the popular demonstrations he attended. Since then, the artist has maintained the importance of three plastic factors: colors, pigments, and the study of light. Each of these factors has been refined over the years, along with the characters and objects he has chosen to represent. Note, for example, that a clear compositional study is dedicated directly to these three elements of plastic analysis, the series Color, Pigment, Light, first produced in 1974.

More broadly, two initiatives stand out in this selection of works, both because of their low profile in recent exhibitions and the expressive power of the signs that make them up. The first is the representation of the “screw” as a protagonist element. There are various forms of presentation, from technical drawing to perspective, from colors to multiple shadows, among others. In a certain sense, all of them focus on a pendulum ratio between the precision of contact, fixation, and union and the metaphor of violence in movement and force. This sophisticated perception of violence is the result of a traumatic reading by those who have actually been under the control of the mechanisms of a state of exception. Curiously, the presence of the “nail” element, a recurring sign in the work of his colleague Carlos Zílio in those same 1970s, is from the same period.

The second, also highlighted, refers to the “interferences” in which images are superimposed using the silkscreen technique or in the suggestion of collages. In these cases, there is a search for graphic accuracy and a radical overlapping of signs that cause noise and strangeness. There is deliberate confusion in the definition of territories that integrate the natural and the built, as well as the disposable and the space of the landscape. These works can be easily paralleled with the North American production of the time and the more radical practices of Brazilian environmental art. Drawing these parallels is a critical exercise after browsing the exhibition.

In some of these works, there is also the representation of what actually exists in a given situation superimposed on another that may not exist, creating falsely real images, such as a combination of train tracks, for example. Also from the same period is the series of pollutions: in these cases, the titles act with the same force of meaning as the superimposed images that were conceived using different reproduction techniques. Thematizing and materializing the very idea of pollution seems to me to be something unprecedented for that moment in the early 1970s.

In the cases in which the object “screw” is brought in, there is a look that happens like a magnifying glass, one that goes into the intricacies of the fitting of the screw itself, in what defines it as such. On the other hand, in the contributions dedicated to the chaotic and overlapping outer space, the gaze is on what is outside, on the city and its most diverse and apparently random developments. It is a critical perception of the uncontrollable contemporary city. In both compositions, there is reverence for time. It is the only unwavering constant, captured momentarily in each image constructed by the artist. It is by observing the indices of time recorded in art that we gain a more accurate understanding of our history, our places, and our exchanges in the collective. As Chico Buarque (Julinho de Adelaide) – a lifelong friend and college classmate of Tozzi – said in the first verse of the song Jorge Maravilha (1974): “There’s nothing like time after a setback.” And that’s why making art is always about fighting for the next new time.

galeria marcelo guarnieri | são paulo

Info: contato@galeriamarceloguarnieri.com.br

Alameda Franca, 1054

São Paulo

[ mapa/map ]